Here’s a confession: I used to think “cutting-edge ocean technology” meant expensive sensors, satellite imaging, and research vessels that cost more than my college tuition.

Then I learned about clam gardens.

And eel weirs. And fishponds that fed entire kingdoms. And I realized that the most sophisticated ocean technology isn’t always found in a lab—sometimes it’s found in a 3,500-year-old rock wall built by Indigenous communities who understood marine ecosystems better than most modern scientists do today.

So grab your metaphorical wetsuit. We’re going on a world tour of Indigenous marine technology that’s so ingenious, scientists are still trying to figure out exactly how it all works.

Clam Gardens: The Backyard Farmers of the Sea (Pacific Northwest)

The Basics:

Imagine you want more clams. What do you do? If you’re part of the Coast Salish peoples of the Pacific Northwest, you don’t just hope for more clams—you literally build them a better home.

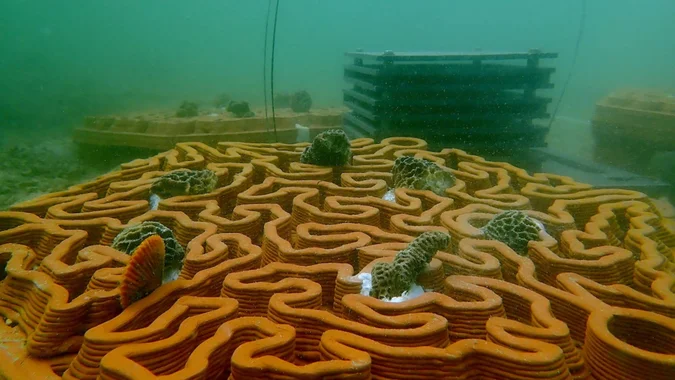

Clam gardens are deceptively simple: Indigenous communities built low rock walls at the lowest tide line along beaches. As sediment accumulated behind these walls, the beach transformed into a gentler slope—basically a clam paradise. The terraced habitat that formed was perfect for butter clams and littleneck clams to thrive.

Mind-Blowing Stats:

- These gardens date back over 3,500 years

- Studies of ancient clam gardens in British Columbia found clam densities 2-4 times higher than on non-gardened beaches

- The Swinomish Indian Tribal Community recently built the first modern clam garden in the United States in Skagit Bay, Washington

- Shell fragments from tended gardens actually help buffer ocean acidification locally (yes, seriously)

Why This Matters:

Here’s the thing that gets me: these gardens weren’t just about growing food. They were climate adaptation technology before we even had a word for climate adaptation. As sea levels changed over millennia, communities simply moved their walls. The gardens are naturally resilient to sea level rise—something we’re desperately trying to engineer today.

When I first read about Swinomish clam gardens, I thought: “Wait, this has been here the whole time?” These weren’t lost to history—the knowledge was there. It just hadn’t been listened to.